The idea of having to handle dead bodies may not sound very appealing to many – what more to have to cut it open and examine its parts.

However, in seeking the truth of how a deceased came to his/her death, somebody has to do it.

Meet Dr Mohammad Sharafi Bin Zaini.

He is one of the few who finds such work interesting and actually has the guts (pun intended) to get the job done.

He also holds a Master’s degree in Forensic Pathology from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

At the time of the interview, he was serving as a clinical forensic specialist at Hospital Kuala Lumpur. However, he has since gone back to Kedah to serve at Hospital Sultanah Bahiyah.

“I don't think forensic is that popular. Even amongst medical practitioners, sometimes, forensic is quite alien for them,” he told us.

However, for him, the interest has always been there as he grew up reading 'Detective Conan', the famous manga series. He is passionate about connecting clues and solving puzzles.

An excellent introductory lecture from renowned forensics specialist, Dato’ Dr Zahari Bin Noor, during his first year in medical school also reinforced his interest to join the field.

Dr Sharafi continued to do his own research about forensic work and concluded that this is what he would like to do.

“In forensics, it’s like, where does this go, where did this come from, how did this person get these injuries, how are you going to reconstruct the chain of events and everything that contribute to this injury. That's the beauty of forensics.”

Upon completing his housemanship in 2009 back in Alor Setar, he met the head of the department and expressed his intention to join the forensic team. And such was the beginning.

There were mixed reactions among his family members when it comes to this particular decision of his.

His mother, in her Kedah dialect, said, “Hang takdak tempat lain ka nak pi? Tengok oghang mati ja ka?” (Do you not have anywhere else to go? Just go and see dead people only?).

Eventually, he gained her support. His late father, on the other hand, was supportive right from the start as he encouraged the act of venturing into a field most wouldn't. His wife simply didn't mind it too much.

He has been in the forensic service for 10 years now. The avid PS4 gamer humbly stated that “10 years is actually quite new”.

There are also instances when he would have to present himself as a professional witness to the court of law to give his statements in front of the judge.

On busy days when there is an influx of dead bodies – which apparently, is called a ‘kenduri’ – he would be busy carrying out post-mortem examinations throughout the day.

His nature of work mainly revolves around medicolegal cases. A medicolegal case, according to Dr Sharafi basically refers to “any case that involves medical and legal issues. It can be of a living person. It can be of a dead person”.

His nature of work mainly revolves around medicolegal cases. A medicolegal case, according to Dr Sharafi basically refers to “any case that involves medical and legal issues. It can be of a living person. It can be of a dead person”.

His work would be with the latter.

“Our core business is doing post-mortem examination as prescribed by the law. The Criminal Procedure Code Sections 330 and 331 mentions the duty of a government medical officer to conduct post-mortem examination,” explained the 37-year-old.

(Fact: Post-mortem essentially means ‘after death’ in Latin. #NowYouKnowLah)

His responsibilities also include overseeing the handling process of corpses as well as deaths at the patient wards. There is also a mortuary under the forensic department’s care.

Dr Sharafi is also part of the team that provides training for junior doctors, medical students and specialists, especially concerning medicolegal issues.

“Everything medicolegal, usually the people will come and ask for our opinion and advice,” he stated.

He also stated that under Section 334, death in custody such as death in lockup, prison or immigration detention centre would also lead to a post-mortem examination.

However, one should note that the police would first investigate such deaths. They will determine whether there is a need for a post-mortem examination.

However, one should note that the police would first investigate such deaths. They will determine whether there is a need for a post-mortem examination.

“If they don't require a post-mortem examination, the police will issue the cause of death themselves.

"That's why, especially in cases for sudden death involving the elderly, you can see that sometimes the cause of death is stated as sakit tua (old age), sakit jantung (heart disease) – very layman terms. According to our law, it is permissible. So, it’s okay,” elaborated Dr Sharafi.

“We wouldn’t conduct any procedure if we don't get that POL 61,” he clarified.

There are two types of post-mortem examination: 1) the medicolegal autopsy or also known as a medical post-mortem examination, which is the regular affair for Dr Sharafi, or 2) a clinical post-mortem examination, which is more towards academic purposes.

In his course of work, the three major elements that need to be established are the cause and mechanism of death, which includes providing assistance to determining the manner of death, collection of evidence, and assisting with identification of the deceased to ease the police in their investigation.

A post-mortem examination is a destructive process. There is only one chance to examine the body, Dr Sharafi said.

“If we missed something, it could actually alter the cause of death or give a different outcome to the investigation and report. That’s why we usually have a short briefing or discussion of what to do and what to take and what to examine before we proceed with the post-mortem examination.

Ideally, there will be four personnel on duty during the process with at least one representative from the police force. Photographs of the process and a draft report make up the documentation and evidence.

The pictures taken during the post-mortem examination are either from the forensic team or the police force.

The post-mortem examination takes on the external and internal part of the body.

“The external examination covers all the belongings and personal defects that the deceased has during that time – what he wears, what he has with him. Let’s say he wears a t-shirt and (a pair of) jeans. Does that t-shirt or clothing have any tear or slip-like effect – something that may indicate injuries that came with the body itself,” he explained.

The aim is to look for injuries. All types of injuries have to be documented and interpreted.

“We have to measure and describe the injuries. Let’s say, this is a laceration wound – where is it, how big is it, which underline structure does it involve, has the bone been fractured along with the wound and so on.”

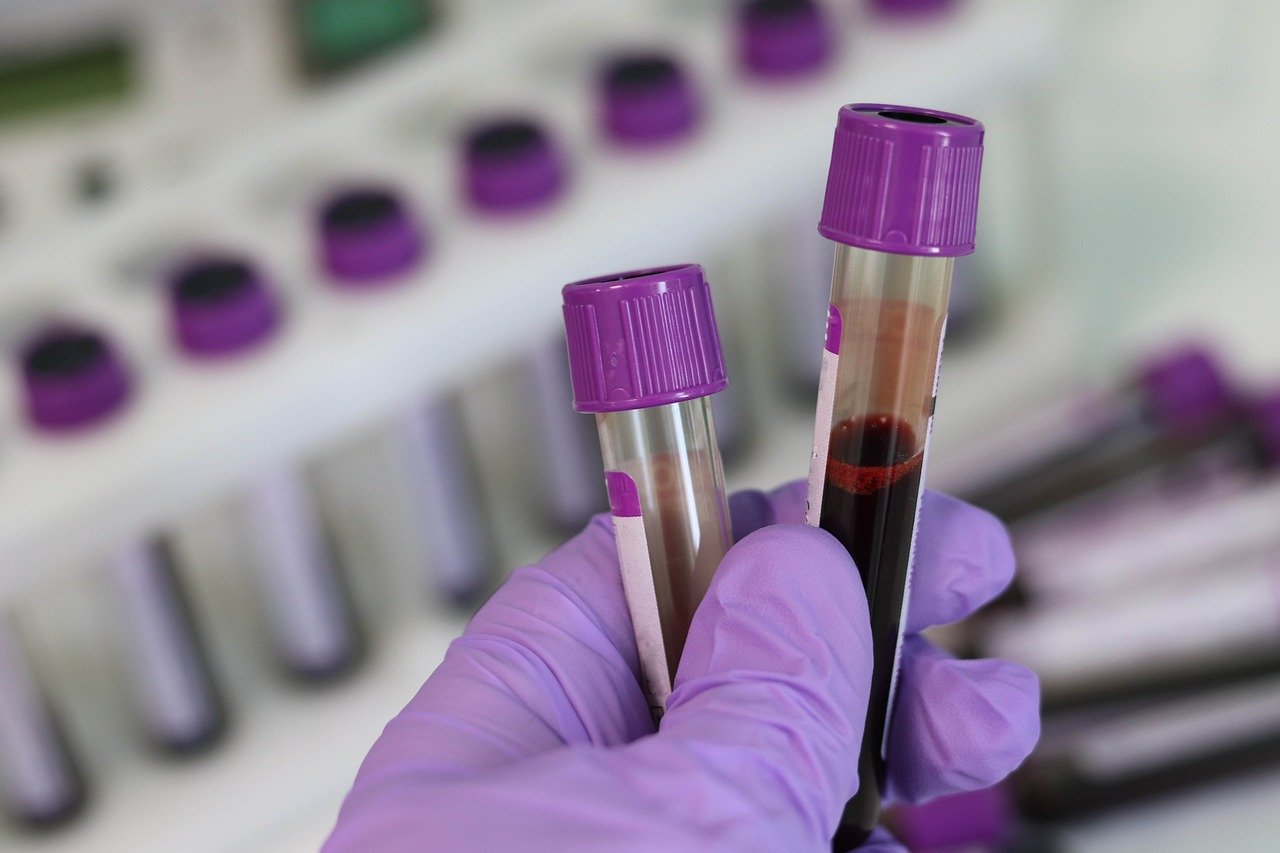

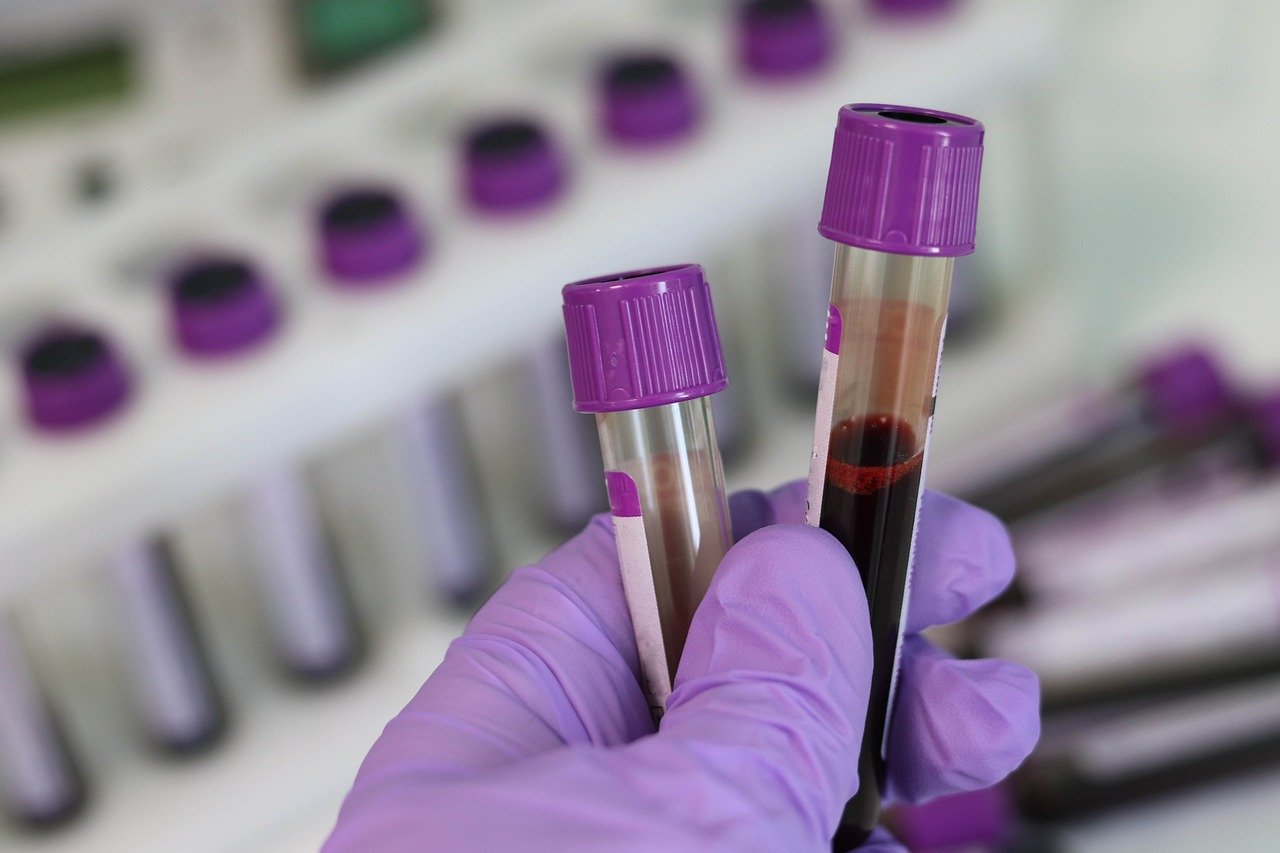

Upon the completion of the external examination, specimens will be collected. It would usually be the blood and urine for toxicology analysis but depending on the case, it could include others that are necessary for the laboratory investigation too.

Upon the completion of the external examination, specimens will be collected. It would usually be the blood and urine for toxicology analysis but depending on the case, it could include others that are necessary for the laboratory investigation too.

Then, it would be time for the internal examination of the body, which basically means the dissection of the body.

“Every organ inside the body must be examined for any injury or disease, correlate with any external injuries if necessary. And yes, the organs are sliced up so that the inside could be examined properly” he further enlightened us.

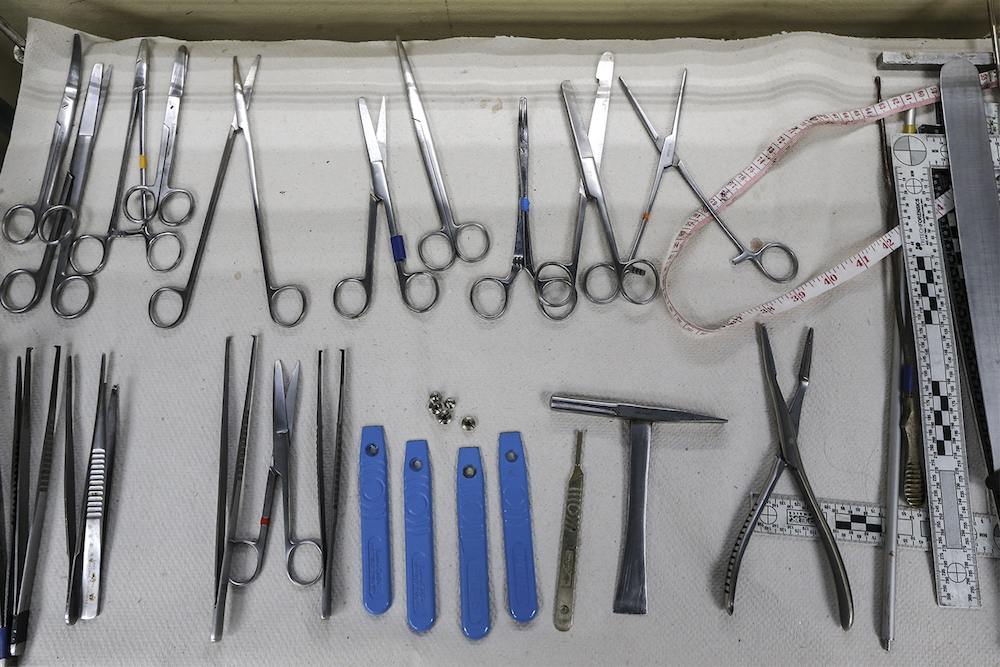

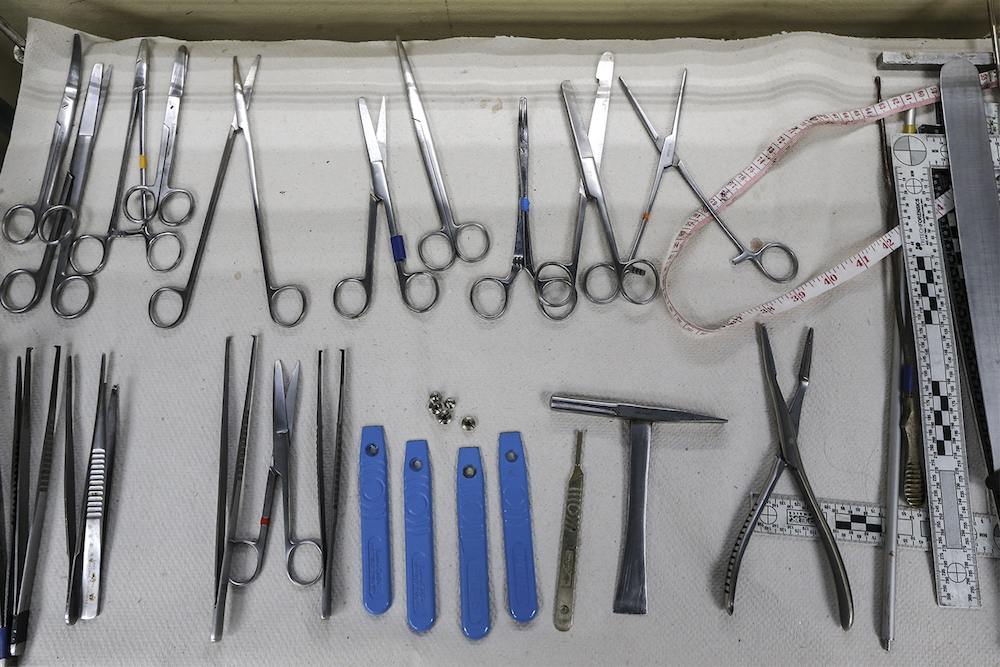

Besides the regular instruments used in an operation theatre, the PM40 knife or also known as the post-mortem knife is one of the signature instruments of a forensic pathologist. It is used to open up almost everything.

“You can even cut the ribs at the cartilage part with the knife because it is that sharp,” disclosed Dr Sharafi.

There is also the skull saw. As the name suggests, it is used to cut open a skull and other bones. The chisel and hammer are also part of the list. We’re squirming just as much as you are!

This release process may take longer should it involve non-Malaysians as it would require more paperwork such as customs clearance and embassy clearance.

On which part is more significant – the external or internal examination – Dr Sharafi answered that it depends on the type of case.

For cases such as sudden death, the internal examination will take longer than its counterpart as they seek to find the cause of death, which would be more evident internally.

However, in homicidal cases, the external examination is the main focus because “…when we have established all the injuries, we would have something in mind on what the internal injuries will be”.

Dr Sharafi also pointed out that for such cases, they have to be more meticulous and detailed on the external injuries. It makes sense, as the external injuries are potential major clues for such events.

ALSO READ:

'We Are The Ghost': An Interview With A Real-Life Malaysian Military Sniper

The duration of the post-mortem examination varies according to cases. It could take two hours to complete or it could stretch up to 12 hours. It could even go on for days.

Upon the completion of the post-mortem examination, the doctors will then form an opinion on the cause of death.

“After conducting the post-mortem examination, we then have to provide a report of the post-mortem examination so that the report can be used as a prima facie evidence in court to ensure the prosecution process and such will go on as smooth as possible,” he added.

It is fair to say that as a forensic pathologist, he acts as the bridge for the dead to tell the story of its death.

Dealing with a dead body is one thing, but dealing with one that is severely decomposed would rattle even the most experienced forensic pathologist.

“We do not only see fresh cases. Sometimes, the body that arrives has been decomposed with worms, bloated and green,” Dr Sharafi revealed.

And of course, on certain occasions, they would have to deal with incomplete bodies. It does go to the extremes such as having a head without a body or vice versa.

In worst cases, they would get only the skeletal remains. The post-mortem examination will still have to be carried out comprehensively but with certain deviations from what they would usually do. It is not for the faint-hearted.

“Let’s say, we examine a bone. We have to determine whether this is a human’s or not, male or female, age determination; whether this bone belongs to an adult or a child or an elderly – and eventually, it will come back to the determination of the most probable cause of death which could get pretty difficult with only the bones,” he stated.

Dr Sharafi and his team will, however, help to establish the identity – usually, by taking DNA and blood sample, fingerprint and sometimes, they would refer the body to the dental team for dental records and odontology examination.

The findings will be formed into a report, which will then be submitted to the police. With all the information gained, it would then be the duty of the investigating officer to trace the identity and find the deceased’s family members

“If the body is not known of any identity, we have to keep it here (at the mortuary) for a while until the police say we can release the body. But usually, the release of the body will need the authorisation letter from the police themselves.”

“If the body is not known of any identity, we have to keep it here (at the mortuary) for a while until the police say we can release the body. But usually, the release of the body will need the authorisation letter from the police themselves.”

He added, “The problem arises when the body is of an unknown person or the police cannot have the identity. If they still couldn't get the identity of the deceased, the police themselves have the power to order for the body to be buried or cremated depending on their procedure.

"It’s not on our side. We just help to keep the body”.

He did, however, said that living people are scarier than the dead. Why?

“There are many ways that people can kill a person. And there are many cases that I’ve seen in which the first thing that came into my mind after seeing the body was, ‘Woi, suspek ni gila ka apa ka (Was this suspect mad or what)’”.

He described some of the conditions of the body as having been overkilled or too gruesome and too brutal. Hence, his conclusion that living people are scarier than dead people – in fact, scarier than ghosts.

And so, of course, we had to ask if he has ever had any ghostly encounters. While he did state that this is not a matter to be emphasised, Dr Sharafi summarised his answer in four words: “Patient saya bagi salam (My patient greeted me)”.

That was enough to give us the chills.

On a more cheerful note, Dr Sharafi reminisced the time he received a 'thank you' card from an appreciative next of kin.

“That was my sweet memory. I still keep the card,” he said with a smile.

However, if there's one thing he doesn't like about his work, it's his experience at the court. Apparently, it is a mutual feeling for many forensic specialists.

The scrutiny and ‘grilling’ during the cross-examination session from the defence lawyers are enough to load some major pressure.

Besides that, there was also a time when Dr Sharafi had to deal with the accusation of selling organs on the black market.

It's absurd, we know.

If you think a mortuary is a scary place and the forensic department is gloomy, well, Dr Sharafi is here to oppose.

“You can see my place – it’s very bright and sweet-smelling too with the air-freshener there.”

True enough, the walls of his office is baby blue in colour and a pleasant scent filled the air.

He also highlighted that “as forensic doctors, we don't handle things like forensic scientists. We don't actually go to the scene as at our own will. We have to be invited by the police before going”.

On top of that, forensic pathologists also do not have the power to launch their own investigation. It doesn't work that way here in Malaysia.

And if you think they need not possess good communication skills, well, think again. Communication skills are essential, as they would have to explain to the family members about the process that will be conducted on their loved ones.

While no consent is required to proceed with the post-mortem examination for medicolegal cases, it is only fair to have and express empathy and understanding.

“We have to explain in a good way,” said Dr Sharafi.

Handling dead bodies on a daily basis, it is safe to say that Dr Sharafi is not easily startled by them. In fact, he admits that he is numbed over the sight of them.

However, there are three particular cases that took a toll on him.

There was once an uncle whom Dr Shafari would frequently buy roti canai from. As fate would have it, the uncle met with an accident and passed away. The body arrived at the forensic department during his shift.

He had to toughen up and perform his duty despite the wife of the deceased begging him not to carry on with the post-mortem examination.

A homicidal case which involved three siblings also hit close to home for Dr Sharafi.

He was also part of the forensic pathology team that dealt with the Tahfiz Darul Quran Ittifaqiyah Centre fire tragedy in 2017 – an incident that shook the nation with the loss of 21 children and two teachers.

Recalling the case, Dr Sharafi said, “I just can’t. It broke me”.

Having seen dead bodies in all sorts of form, we asked for his perspective on the value of life.

After a short pause to reflect on it, Dr Sharafi said: “We can die anytime so cherish your loved ones”.

However, in seeking the truth of how a deceased came to his/her death, somebody has to do it.

Meet Dr Mohammad Sharafi Bin Zaini.

He is one of the few who finds such work interesting and actually has the guts (pun intended) to get the job done.

Connecting clues and solving puzzles

Born in Butterworth, Penang but bred in Kulim, Kedah, Dr Sharafi obtained his undergraduate medical degree from Universiti Islam Antarabangsa Malaysia.He also holds a Master’s degree in Forensic Pathology from Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia.

At the time of the interview, he was serving as a clinical forensic specialist at Hospital Kuala Lumpur. However, he has since gone back to Kedah to serve at Hospital Sultanah Bahiyah.

“I don't think forensic is that popular. Even amongst medical practitioners, sometimes, forensic is quite alien for them,” he told us.

However, for him, the interest has always been there as he grew up reading 'Detective Conan', the famous manga series. He is passionate about connecting clues and solving puzzles.

An excellent introductory lecture from renowned forensics specialist, Dato’ Dr Zahari Bin Noor, during his first year in medical school also reinforced his interest to join the field.

Dr Sharafi continued to do his own research about forensic work and concluded that this is what he would like to do.

“In forensics, it’s like, where does this go, where did this come from, how did this person get these injuries, how are you going to reconstruct the chain of events and everything that contribute to this injury. That's the beauty of forensics.”

Upon completing his housemanship in 2009 back in Alor Setar, he met the head of the department and expressed his intention to join the forensic team. And such was the beginning.

There were mixed reactions among his family members when it comes to this particular decision of his.

His mother, in her Kedah dialect, said, “Hang takdak tempat lain ka nak pi? Tengok oghang mati ja ka?” (Do you not have anywhere else to go? Just go and see dead people only?).

Eventually, he gained her support. His late father, on the other hand, was supportive right from the start as he encouraged the act of venturing into a field most wouldn't. His wife simply didn't mind it too much.

He has been in the forensic service for 10 years now. The avid PS4 gamer humbly stated that “10 years is actually quite new”.

All in a day's work

On a typical day, Dr Sharafi could be found at his desk typing out reports for the post-mortem examinations performed. Other times, he would be giving statements to the police for the cases he is in charge of.There are also instances when he would have to present himself as a professional witness to the court of law to give his statements in front of the judge.

On busy days when there is an influx of dead bodies – which apparently, is called a ‘kenduri’ – he would be busy carrying out post-mortem examinations throughout the day.

His nature of work mainly revolves around medicolegal cases. A medicolegal case, according to Dr Sharafi basically refers to “any case that involves medical and legal issues. It can be of a living person. It can be of a dead person”.

His nature of work mainly revolves around medicolegal cases. A medicolegal case, according to Dr Sharafi basically refers to “any case that involves medical and legal issues. It can be of a living person. It can be of a dead person”.His work would be with the latter.

“Our core business is doing post-mortem examination as prescribed by the law. The Criminal Procedure Code Sections 330 and 331 mentions the duty of a government medical officer to conduct post-mortem examination,” explained the 37-year-old.

(Fact: Post-mortem essentially means ‘after death’ in Latin. #NowYouKnowLah)

His responsibilities also include overseeing the handling process of corpses as well as deaths at the patient wards. There is also a mortuary under the forensic department’s care.

Dr Sharafi is also part of the team that provides training for junior doctors, medical students and specialists, especially concerning medicolegal issues.

“Everything medicolegal, usually the people will come and ask for our opinion and advice,” he stated.

Classifying a death

Dr Sharafi explained that under the Criminal Procedure Code Section 329, there is a list of death cases that requires investigation by the police. They include but are not limited to:- Any suicidal case

- Any homicidal case

- Any death by accident in which the definition of accident is vast such as motor vehicle accident, falling from a height, drowning and electrocution

- Any death that raises suspicion

- Any body found dead, particularly in public area

- Death caused by animal

- Death caused by machinery

- Sudden death

He also stated that under Section 334, death in custody such as death in lockup, prison or immigration detention centre would also lead to a post-mortem examination.

However, one should note that the police would first investigate such deaths. They will determine whether there is a need for a post-mortem examination.

However, one should note that the police would first investigate such deaths. They will determine whether there is a need for a post-mortem examination.“If they don't require a post-mortem examination, the police will issue the cause of death themselves.

"That's why, especially in cases for sudden death involving the elderly, you can see that sometimes the cause of death is stated as sakit tua (old age), sakit jantung (heart disease) – very layman terms. According to our law, it is permissible. So, it’s okay,” elaborated Dr Sharafi.

Getting down to business

Dr Sharafi told us that the body could arrive at the forensic centre at any time – be it morning, evening or even in the wee hours. The body could come with or without the issuance of POL 61, an order from the police for a post-mortem examination to be performed.“We wouldn’t conduct any procedure if we don't get that POL 61,” he clarified.

There are two types of post-mortem examination: 1) the medicolegal autopsy or also known as a medical post-mortem examination, which is the regular affair for Dr Sharafi, or 2) a clinical post-mortem examination, which is more towards academic purposes.

In his course of work, the three major elements that need to be established are the cause and mechanism of death, which includes providing assistance to determining the manner of death, collection of evidence, and assisting with identification of the deceased to ease the police in their investigation.

A post-mortem examination is a destructive process. There is only one chance to examine the body, Dr Sharafi said.

“If we missed something, it could actually alter the cause of death or give a different outcome to the investigation and report. That’s why we usually have a short briefing or discussion of what to do and what to take and what to examine before we proceed with the post-mortem examination.

Ideally, there will be four personnel on duty during the process with at least one representative from the police force. Photographs of the process and a draft report make up the documentation and evidence.

The pictures taken during the post-mortem examination are either from the forensic team or the police force.

The post-mortem examination takes on the external and internal part of the body.

“The external examination covers all the belongings and personal defects that the deceased has during that time – what he wears, what he has with him. Let’s say he wears a t-shirt and (a pair of) jeans. Does that t-shirt or clothing have any tear or slip-like effect – something that may indicate injuries that came with the body itself,” he explained.

The aim is to look for injuries. All types of injuries have to be documented and interpreted.

“We have to measure and describe the injuries. Let’s say, this is a laceration wound – where is it, how big is it, which underline structure does it involve, has the bone been fractured along with the wound and so on.”

Upon the completion of the external examination, specimens will be collected. It would usually be the blood and urine for toxicology analysis but depending on the case, it could include others that are necessary for the laboratory investigation too.

Upon the completion of the external examination, specimens will be collected. It would usually be the blood and urine for toxicology analysis but depending on the case, it could include others that are necessary for the laboratory investigation too.Then, it would be time for the internal examination of the body, which basically means the dissection of the body.

“Every organ inside the body must be examined for any injury or disease, correlate with any external injuries if necessary. And yes, the organs are sliced up so that the inside could be examined properly” he further enlightened us.

A pathologist's instruments

Besides the regular instruments used in an operation theatre, the PM40 knife or also known as the post-mortem knife is one of the signature instruments of a forensic pathologist. It is used to open up almost everything.

“You can even cut the ribs at the cartilage part with the knife because it is that sharp,” disclosed Dr Sharafi.

There is also the skull saw. As the name suggests, it is used to cut open a skull and other bones. The chisel and hammer are also part of the list. We’re squirming just as much as you are!

The duration of a post-mortem

After examining the internal organs and documenting the process and findings, the body will be sewn closed, cleaned and properly handled before it is released to the family or next of kin.This release process may take longer should it involve non-Malaysians as it would require more paperwork such as customs clearance and embassy clearance.

On which part is more significant – the external or internal examination – Dr Sharafi answered that it depends on the type of case.

For cases such as sudden death, the internal examination will take longer than its counterpart as they seek to find the cause of death, which would be more evident internally.

However, in homicidal cases, the external examination is the main focus because “…when we have established all the injuries, we would have something in mind on what the internal injuries will be”.

Dr Sharafi also pointed out that for such cases, they have to be more meticulous and detailed on the external injuries. It makes sense, as the external injuries are potential major clues for such events.

ALSO READ:

'We Are The Ghost': An Interview With A Real-Life Malaysian Military Sniper

The duration of the post-mortem examination varies according to cases. It could take two hours to complete or it could stretch up to 12 hours. It could even go on for days.

Upon the completion of the post-mortem examination, the doctors will then form an opinion on the cause of death.

“After conducting the post-mortem examination, we then have to provide a report of the post-mortem examination so that the report can be used as a prima facie evidence in court to ensure the prosecution process and such will go on as smooth as possible,” he added.

It is fair to say that as a forensic pathologist, he acts as the bridge for the dead to tell the story of its death.

Dealing with dead bodies

Dealing with a dead body is one thing, but dealing with one that is severely decomposed would rattle even the most experienced forensic pathologist.

“We do not only see fresh cases. Sometimes, the body that arrives has been decomposed with worms, bloated and green,” Dr Sharafi revealed.

And of course, on certain occasions, they would have to deal with incomplete bodies. It does go to the extremes such as having a head without a body or vice versa.

In worst cases, they would get only the skeletal remains. The post-mortem examination will still have to be carried out comprehensively but with certain deviations from what they would usually do. It is not for the faint-hearted.

“Let’s say, we examine a bone. We have to determine whether this is a human’s or not, male or female, age determination; whether this bone belongs to an adult or a child or an elderly – and eventually, it will come back to the determination of the most probable cause of death which could get pretty difficult with only the bones,” he stated.

What happens to unidentified ones?

“On our side, technically, we don't have the authority to investigate the identity of the deceased. That's actually the police’s work,” he said.Dr Sharafi and his team will, however, help to establish the identity – usually, by taking DNA and blood sample, fingerprint and sometimes, they would refer the body to the dental team for dental records and odontology examination.

The findings will be formed into a report, which will then be submitted to the police. With all the information gained, it would then be the duty of the investigating officer to trace the identity and find the deceased’s family members

“If the body is not known of any identity, we have to keep it here (at the mortuary) for a while until the police say we can release the body. But usually, the release of the body will need the authorisation letter from the police themselves.”

“If the body is not known of any identity, we have to keep it here (at the mortuary) for a while until the police say we can release the body. But usually, the release of the body will need the authorisation letter from the police themselves.”He added, “The problem arises when the body is of an unknown person or the police cannot have the identity. If they still couldn't get the identity of the deceased, the police themselves have the power to order for the body to be buried or cremated depending on their procedure.

"It’s not on our side. We just help to keep the body”.

'Patient saya bagi salam'

While the sight of dead bodies would leave many scared (and possibly, scarred for life), Dr Sharafi has long come to terms with it.He did, however, said that living people are scarier than the dead. Why?

“There are many ways that people can kill a person. And there are many cases that I’ve seen in which the first thing that came into my mind after seeing the body was, ‘Woi, suspek ni gila ka apa ka (Was this suspect mad or what)’”.

He described some of the conditions of the body as having been overkilled or too gruesome and too brutal. Hence, his conclusion that living people are scarier than dead people – in fact, scarier than ghosts.

And so, of course, we had to ask if he has ever had any ghostly encounters. While he did state that this is not a matter to be emphasised, Dr Sharafi summarised his answer in four words: “Patient saya bagi salam (My patient greeted me)”.

That was enough to give us the chills.

On a more cheerful note, Dr Sharafi reminisced the time he received a 'thank you' card from an appreciative next of kin.

“That was my sweet memory. I still keep the card,” he said with a smile.

However, if there's one thing he doesn't like about his work, it's his experience at the court. Apparently, it is a mutual feeling for many forensic specialists.

The scrutiny and ‘grilling’ during the cross-examination session from the defence lawyers are enough to load some major pressure.

Besides that, there was also a time when Dr Sharafi had to deal with the accusation of selling organs on the black market.

It's absurd, we know.

It is not all dark and gloomy

Dr Sharafi also addressed several other common misconceptions the society has towards his profession.If you think a mortuary is a scary place and the forensic department is gloomy, well, Dr Sharafi is here to oppose.

“You can see my place – it’s very bright and sweet-smelling too with the air-freshener there.”

True enough, the walls of his office is baby blue in colour and a pleasant scent filled the air.

He also highlighted that “as forensic doctors, we don't handle things like forensic scientists. We don't actually go to the scene as at our own will. We have to be invited by the police before going”.

On top of that, forensic pathologists also do not have the power to launch their own investigation. It doesn't work that way here in Malaysia.

And if you think they need not possess good communication skills, well, think again. Communication skills are essential, as they would have to explain to the family members about the process that will be conducted on their loved ones.

While no consent is required to proceed with the post-mortem examination for medicolegal cases, it is only fair to have and express empathy and understanding.

“We have to explain in a good way,” said Dr Sharafi.

Putting aside his emotions

Handling dead bodies on a daily basis, it is safe to say that Dr Sharafi is not easily startled by them. In fact, he admits that he is numbed over the sight of them.

However, there are three particular cases that took a toll on him.

There was once an uncle whom Dr Shafari would frequently buy roti canai from. As fate would have it, the uncle met with an accident and passed away. The body arrived at the forensic department during his shift.

He had to toughen up and perform his duty despite the wife of the deceased begging him not to carry on with the post-mortem examination.

A homicidal case which involved three siblings also hit close to home for Dr Sharafi.

He was also part of the forensic pathology team that dealt with the Tahfiz Darul Quran Ittifaqiyah Centre fire tragedy in 2017 – an incident that shook the nation with the loss of 21 children and two teachers.

Recalling the case, Dr Sharafi said, “I just can’t. It broke me”.

Having seen dead bodies in all sorts of form, we asked for his perspective on the value of life.

After a short pause to reflect on it, Dr Sharafi said: “We can die anytime so cherish your loved ones”.